Features

Genetics

Hatchery Operations

Technology

Finding success in an unlikely space

With five land-based farms and two sea sites in Chile, Aquagen has been producing salmon roe all year ‘round, in a country known for its natural disasters

November 11, 2021 By Christian Pérez-Mallea

Aquagen has invested in different and distant production facilities in Chile, to reduce risks and not affect the egg supply due to natural disasters or disease outbreaks.

Photos: Aquagen Chile

Aquagen has invested in different and distant production facilities in Chile, to reduce risks and not affect the egg supply due to natural disasters or disease outbreaks.

Photos: Aquagen Chile On April 22, 2015, the most recent eruption of the Calbuco volcano, located in southern Chile, took place. This affected eight land-based salmon farms in the surrounding area and represented losses of around 773 tons of the whole local industry. This was a game-changing event for most freshwater facility-owners located in the region of Los Lagos, including Aquagen Chile.

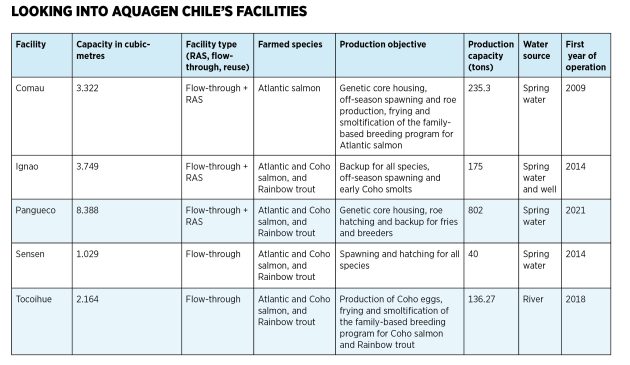

Six years later, the company operates five land-based facilities in the country with a combined total capacity close to 18,650 cubic-metres. Located in separate geographical areas, each of the facilities share similarities and differences. For example, some use recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) technologies, while others run with flow-through water systems.

Not only is this the only long-lasting salmon genetics and breeding company in Chile, but it is also the one with the largest share in the domestic market. The firm has been supplying the local salmon industry since 2000.

Multiple eggs in multiple baskets

Aquagen Chile had about 70 per cent of its Coho salmon egg production concentrated in the hatchery ‘Río Sur’ until 2015, when the facility was destroyed due to the eruption of Calbuco.

The general manager of the company, Patrick Dempster, explained that following the eruption, Aquagen’s board of directors decided to invest in several operating units in Chile, both owned and leased, to offer its customers certainty regarding the egg supply.

“This is why we have incubation in three sites; the genetic nuclei of Atlantic salmon are tripled; those of Coho and trout, are duplicated; and the breeding stock, duplicated too. Not only in quantity, but also in different locations, so if there is a complete loss of any of them, the impact on the total supply of eggs for the year is not affected,” he said.

Similarly, the company rears breeders at two sea sites, Pumalín and Quetén, whose populations are practically copies of each other, so if one fails, it is possible to take the fish from the other site.

On top of the above, in terms of genetic progress, having two completely different farms allowed a more precise and advanced improvement by selecting those brood candidates that perform the best under those two different environmental conditions.

Breeders at sea sites

A good part of Aquagen’s breeders in Chile have been reared at marine sites like those used by their clients. That means those breeders are exposed to the same challenges that their offspring will face at the farms of Aquagen’s clients (disease pressure, parasites, low dissolved oxygen, algae blooms, toxins, gill problems, smoltification, etc.). However, being in the real environment might pose some biosecurity risks. These are not assumed by the clients, due to the very intensive screening procedures the Chilean and customers impose; in a case that any disease is found in those breeders, they are eliminated and do not produce eggs. The genetic benefits of a higher and more accurate selection in the real commercial environment, expressed in better genetic progress, largely outweighs the small chance of screening failures.

“This practice not only allows for us to make a more precise selection, but we can also maintain a larger number of individuals. This capability allows us to apply a much stronger selection intensity than in closed systems, leading to greater genetic gain, generation after generation,” said Cristhian Ortiz, commercial manager of Aquagen Chile.

He continued to explain that this strong intensity selection allows them to achieve a higher rate of genetic progress per unit of time. “This greater genetic progress translates into a constant influx of improvements to the industry that has been verified in the field, with the excellent results of our strain in recent years, both in terms of growth and in terms of robustness and resistance to diseases,” he said. “For example, most of those Atlantic salmon farmed in Chile without using antibiotics, belong to the Aquagen strain,” he added.

RAS or flow-through?

One of the main objectives of the company is to produce eggs throughout the year. “To achieve that objective, we use recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) technology, which allows us to manage temperature and photoperiod, in order to deliver adequate signals and to control the moment of maturity, thus obtaining eggs when we need,” Ortiz explained.

Moreover, he said that RAS technology allows them to have greater biosecurity control. Since the system requires smaller amounts of water, facility workers can have more control of the entrance of pathogens into the system. “This is how the ‘Comau’ farm has stayed free of pathogens for the past three years,” he revealed.

Meanwhile, Dempster continued to say that “all of our RAS capacity is used to produce off-season eggs. It does not make sense to allocate an expensive infrastructure and operation to produce eggs within the season if you can do it with a system that is cheaper, as in the case of flow-through,” he said.

High performance

Aquagen Chile has been steadily increasing its market share over the past 10 years, from 15 per cent to around 45 per cent in the local market for Atlantic salmon eggs, and up to around 35 per cent for Coho salmon and rainbow trout. Some of its main fully committed customers are Australis, Blumar, Ventisqueros, and Salmones Austral among others

According to Ortiz, their market share has grown because of the excellent genetic performance and implementation of new knowledge in their products, as well as their “strong investment in research and development,” he added.

With investments close to US $16 million over the past eight years, Aquagen has achieved significant progress in resistance to diseases such as Salmon Rickettsial Syndrome (SRS) and infectious pancreatic necrosis (IPN) in Atlantic salmon; as well as SRS in Coho. “Likewise, genetic markers have been identified and implemented to reduce the risks of maturity and, above all, we have managed to implement and validate genomic selection technology that has been applied in our products since 2019,” Ortiz revealed.

In turn, Dempster continued: “Considering that our Atlantic salmon strain has a 45 per cent market share, if the strain behaved the same as any other, one would expect that, by sheer probability, there should be 45 per cent of the Aquagen strain in the best performing farms. However, if you look at the benchmarks selecting the best performing farms in the industry, the Aquagen strain presence is well above 45 per cent,” he stated.

All of the above shows that serious work in genetics, despite slower than other tools, it makes it possible to progressively advance towards a more predictable, efficient and, above all, more sustainable management, even in a country highly exposed and vulnerable to multiple hazards with such as algae blooms, earthquakes, volcanic activity, and tsunamis. Despite all these uncertainties associated with unpredictable natural disasters, Aquagen has committed investments through specific strategic decisions for Chile so that the impact of these risks is minimized.

Print this page